Hidden in the bright light of our time; buried by an unwillingness to learn from history; shrouded in the refuse of the past, the statue of Chief Justice Roger Taney sits quietly in unforgiving prominence outside the State House of Maryland. Reasonable questions are being asked about the motives that led to the placement; succinct arguments are presented for the removal of the offending monument, but, the complexity of history compels the interested parties to set forth their own unique and individual solutions prior to defining the problem, and thereby, confound and confuse any potential educational dialogue.

[Maryland State House, Annapolis. Roger B. Taney in front beneath the dome under trees]

For those, who by chance of birth or by intellectual abhorrence, view the memory of the racist judge as an abomination before God, any discussion about the issues of lifetime are secondary and irrelevant to the end goal of removal. For those, who might propose to enter into a discussion about slavery, and its tentacles of evil which reach even to us today, any conversation is attacked as a support of the man’s dreadful legal contortion. In the light of history, we judge him, by standards we currently hold and without listening to those who knew him

The removal without discussion, and hoped for learning, simply white-washes the past. Judging Taney, a complex man, is a perilous exercise, as is judging Lincoln or Jefferson, Washington or Marshall, if we use only the emotions of the present seen through the spectacle of sixty-second history sound bites and factoids. “Taney also became involved in projects to aid American blacks. He was no abolitionist, but did believe that slavery was an unfortunate institution and should be ended someday.” Like Lincoln, “He (Taney) supported the African colonization movement for free blacks and measures to protect free blacks from unscrupulous slavers who would kidnap them for sale as slaves in the lower South, freed his own slaves, and was always kind and attentive to their interests. Yet while he agreed that slavery must be ended, he believed that it must be done slowly and solely by the actions of the individual states. He was deeply concerned all his life that the federal government would intrude and end slavery abruptly and destroy the South.”

[1] [Roger B. Taney]

This idea that of slow non-federal-government abolition was in keeping with other revolutionary progressive moderate thinkers such as John Marshall, the first Chief Justice who was noted for his humane treatment as a slave master. And yet even with Marshall’s intentional avoidance of the question of slavery, it is Taney who judged but the horrendous decision of Dred Scott. Meanwhile, we conveniently forget the details of Marshall and slavery. “He (Marshall) had no trouble with slavery either. Marshall's sanguine attitude toward slavery clearly disturbs Newmyer, for Marshall devoted almost no mental energy to and found no moral fault with slavery (pp. 414-434). As Newmyer succinctly puts the case, Marshall "showed little interest in the subject" (p. 416).[8] This disinterest had consequences; for at no point did Marshall's Court show the slightest concern for the constitutional nature of slavery. When Mima Queen v. Hepburn, 11 U.S. [7 Cranch] 290 (1813), gave the Court a chance to place human rights before property rights, only Justice Gabriel Duvall (Prince George’s County) argued, "It will be universally admitted, that the right to freedom is more important than the right of property" (p. 428). Unfortunately the rest of the Court, including Chief Justice Marshall, did not hold to this universal value; for Marshall, property rights always came first. As Newmyer concludes of The Antelope, 23 U.S. [10 Wheaton] 66 (1825), "property trumped freedom again" (p. 433) [See Paul Finkelman, An Imperfect Union: Slavery, Federalism, and Comity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1981), and Thomas D. Morris, Southern Slavery and the Law, 1619-1860 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996).]

[2]The whole idea that we can properly place blame on Taney and then find convenient ways to excuse the other southern revolutionaries seems unreasonable to me. Except for John Adams and his son John Quincy Adams, our whole pantheon is loaded with men at least as offensive, with our modern views, as Maryland’s Roger Taney. I suggest that obscuring and ignoring does not help heal the deep wounds and pain that we inherit from slavery, If we are to write an American history then we must address the great conundrum of the revolutionary ideals of America and its unspeakable facts. Trying to juggle the contradictions is a dynamic best served by constant conversation.

[Ship's Bell from the Battleship USS Maryland, in front statue of Chief Justice Taney]

And it was Taney, not Marshall, who when compelled but past legal decisions found in “Rhodes v. Bell, 2 How. 397, 43 U.S. 397, 11 L.Ed. 314 (U.S.Dist.Col.,1844)(The District of Columbia being still governed by the laws of Maryland and Virginia which were in force anterior to the cession, it is not lawful for an inhabitant of Washington county to purchase a slave in Alexandria county and bring him into Washington county for sale; if he does the slave will become entitled to his freedom)”.

[3]The contrast is one of studied avoidance and an ultimately disastrous, evil decision. “In contrast, Marshall, when faced with the question, (including, among others, the mamie queen, and scott v. ben cases which Paul cites), narrowly construed, indeed essentially eliminated, legal rights to manumission which American slaves did have 1) under state antiimportation statutes, essentially reading these statutes as unreasonably hypertechnical forfeitures of the slaveowners' property interests), and 2) in the mamie queen case, interpreting federal hearsay law so narrowly as to exclude the only evidence (family oral history) that slaves generally had to prove the free status of their matrilineal ancestors. (slave status descended through the maternal line).”

[4] [John Marshall] USNPS

“As a contrast to Marshall's parched interpretation of legal rights to manumission, see e.g., the Taney (yes Taney) court opinion of Rhodes v. Bell, 43 US 397 (1844) in which the Taney court (opinion McLean) unanimously freed a slave, holding that manumission provisions in Virginia and Maryland antiimportation laws were applicable in the District of Columbia, narrowly construing an apparently contrary Congessional statute in the process.”

[5]

[Roger Taney in front of Maryland State House]

Unlike Jefferson who never freed his slaves, and unlike Washington who waited until he and his wife were dead, or Marshall, who “…only freed one in his will, his long time personal slave. However, some have argued that the conditions on manumission were such that it was very unlikely that the gentleman would have taken advantage of the generosity. Marshall's will provided that the slave (who had been given to Marshall by his father 52 yeares earlier) would receive 100 dollars if he went to liberia and $50 if he remained in the United States, and if it was "impracticable" for him to leave that he could reside with one of Marshall's children (which I think Robin did - after all, how far are you going to get as a free elderly ex-slave on $50. (even in the 1830s))”

[6] Roger B. Taney, while he was young and alive “…manumitted the slaves inherited from his father, and as long as they lived, he provided for the older ones by monthly pensions.”

[7] Are we to ignore this, and condemn him while excusing others? History is rarely convenient and always painful. Truth is just beyond the next fact; choosing to limit the scope of the conversation serves no one. Using Taney as an instrument to have a true and binding discussion about slavery to create a authentic American history is a gift we can offer here in Maryland. The unwilling partnership is the story of this country; for too long we wrote only of Euro-centric facts. Today we have ethnic origin studies, an entire list of studies, but one must look hard for a combined joint story, good and bad, together as one common received American story.

Unlike Jefferson, who wrote about the enslaved population under the heading of “Animals” in his only book: Notes on the State of Virginia

[8], Roger Taney could be remarkably advanced for his time. “While Taney distrusted the power of great aggregations of wealth in corporate form and believed that the state needed some authority to police such power, he also recognized the advantages to the American economy of the corporations' success and the need for the Court to protect their interests in the American economic system.”

[9] As early as, Taney worked within the law which, being a two edged sword sometimes placed him on the side of right. “Invoking freedom of speech, Taney won acquittal in 1819 for a Methodist preacher whose sermon on national sins provoked the charge of trying to stir up slave rebellion”

[10] [Roger Taney]

The trouble and challenge when considering Taney is that he was not an original thinker, but rather looked to the fundamental understanding of stare decisis to help him render a position. In other words he tended to accept racist positions and then construe legal positions dependent on the thinking and thoughts of others who came before him continue the construction of a racist ideology.

Taney rose to prominence in Maryland, by finding a radically moderate path based upon the idea that laws should change gradually and be based upon precedence. “As a result he was chosen in 1816 for a five-year term in the state Senate, where he ousted the opposing faction from control and dominated the Federalist Party during the few years in which it continued to survive. His major interest, apart from the issues of party politics, seems to have been in laws to prevent the evils due to unsound currency and bad banking, and in laws to protect the rights of negroes in the state, whether freemen or slaves.”

[11]Taney’s work for and with President Jackson was that of a defender of the “little” man against great wealth and power. “While a member of the state Senate he sponsored legislation to prevent the circulation of bank notes at less than their face value, and to prevent the deliberate depreciation of the value of the notes of rural banks for which Baltimore bankers and brokers were said to be in part responsible.”

[12] Roger Taney was instrumental in breaking the power of the national bank. “When he entered the Jackson cabinet he held the conviction that if the institution was to be rechartered it must be with definite limitations on its powers. He so advised the President, and when the friends of the bank attempted at the session of Congress of 1831-32 to force the enactment of a law granting a on the other Taney, who in 1831, “reigned his office as state attorney general, which he had held since 1827, in order to accept an appointment in President Jackson's Cabinet as attorney general. Among his opinions as attorney general, two revealed his stand on slavery: one supported South Carolina's law prohibiting free Blacks from entering the state, and one argued that Blacks could not be citizens.

[13] This then is the basis for Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) decision which would come later.”

[14]Today, we focus on the single defining issue of that time. “Taney did not fit a heroic mold; but his mind was acute, his pen lucid. His patience, tact, and ability were instrumental in overcoming personal and doctrinal divisions among the justices, and though the Court was frequently divided, it continued to administer the law effectively. Under Taney's leadership the Court showed more tolerance of legislative power than it had under Marshall, but it did not surrender its hard-won powers to decide.

[15] [Roger Taney]

“The issue of slavery was the downfall of the Court and detracted permanently from the image of Taney's statesmanship. In Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) Taney wrote the majority opinion for a bitterly divided Court which unwisely confronted all the explosive political questions in the case. Blacks, he said in a racist vein that has since been irrevocably associated with his name, could not be a citizen of the United States because he was recognized as inherently unequal by the Constitution. Congress, moreover, could not prohibit slavery in the territories because the 5th Amendment to the Constitution protected citizens in the possession of their property, and slaves were property.”

[16]Chief Justice Taney clearly outlined the problem which we face today in trying to come to terms with the founding of this republic. “The framers of the United States Constitution believed that people of African descent “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect,” and that “the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit…. [to be] bought and sold and treated as an ordinary article of merchandise and traffic, whenever profit could be made by it.” With reference to the words “all men are created equal” in the Declaration of Independence: “It is too clear for dispute that the enslaved African race was not intended to be included, and formed no part of the people who framed and adopted this declaration.”

[17] How then are we to judge him as the monster incarnate and then give Jefferson and Washington a pass? Roger Taney arouses the hatred of those who believe in the ideals and truths of the Declaration of Independence when he wrote: “It is difficult at this day to realize the state of public opinion in regard to that unfortunate race which prevailed in the civilized and enlightend portions of the world at the time of the Declaration of Independence, and when the Constitution of the United States was framed and adopted; but the public history of every European nation displays it in a manner too plain to be mistaken. They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations, and so far unfit that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect."--from Taney's ruling

[18]So the issue is greater than Taney who bears the burden for not being greater than his time. “Jefferson didn't mean it when he wrote that all men are created equal," writes historian John Hope Franklin. "We've never meant it. The truth is that we're a bigoted people and always have been. We think every other country is trying to copy us now, and if they are, God help the world." He argues that, by betraying the ideals of freedom, "the Founding Fathers set the stage for every succeeding generation of Americans to apologize, compromise, and temporize on those principles."

[19]

[

Roger Taney; Md State House] Some would point out Taney’s contentious disagreements with Lincoln over presidential powers which echo down the ravines of history. Analogies can be dangerous, but the same people who would attack the current president and his right to wage war, would have found that Taney would have nee strongly in their camp. “Justice Robert C. Grier spoke for himself, Wayne, and Lincoln’s three appointees: The President had to meet the war as "it presented itself, without waiting for Congress to baptize it with a name"; and rebellion did not make the South a sovereign nation. Four dissenters said the conflict was the President’s "personal war" until Congress recognized the insurrection on July 13, 1861.

[20]Justice Benjamin Robbins Curtis, author of the dissent on Dred Scott, held his former colleague in high esteem despite their differences in that case. Writing in his own memoirs, Curtis described Taney: “He was indeed a great magistrate, and a man of singular purity of life and character. That there should have been one mistake in a judicial career so long, so exalted, and so useful is only proof of the imperfection of our nature. The reputation of Chief Justice Taney can afford to have anything known that he ever did and still leave a great fund of honor and praise to illustrate his name. If he had never done anything else that was high, heroic, and important, his noble vindication of the writ of habeas corpus, and of the dignity and authority of his office, against a rash minister of state, who, in the pride of a fancied executive power, came near to the commission of a great crime, will command the admiration and gratitude of every lover of constitutional liberty, so long as our institutions shall endure.”

[21]Chief Justice Taney, who remained loyal to the Union, died, aged 87, in October 1864, the same day his beloved state of Maryland, 220 years and six months after legalizing slavery, abolished the peculiarly evil institution.. Lincoln’s Attorney General Edward Bates wrote that his "great error" in the Dred Scott case should not forever "tarnish his otherwise well earned fame." And not long after Taney’s death, victory for the Union brought vindication of his defiant stand for the rule of law.”

[22] [picture below is of Justice Thurgood Marshall in the mall on the otherside of the State house]

Let us then boldly speak of the complexities of men, of the good and the bad. And if the discussion moves us to direct our attention away from Roger Taney and place his monument a little closer to the dark, let us not think that we do not hear his foot steps. We can not ignore history; we can not pretend that evil did not exist, and worse we must never forget, but use the dead ends of history to enlighten our choices in the hope that we can find our way. Move the statue if you must, but not without a conversation. Think of an alternative, whereby we move Justice Taney to one side peering into a dark, dead end corner and stand Frederick Douglas looking into the light directing us to consider the differences and what might have been; a dialogue between good and bad choices.

***********************************************************************************

Notes:

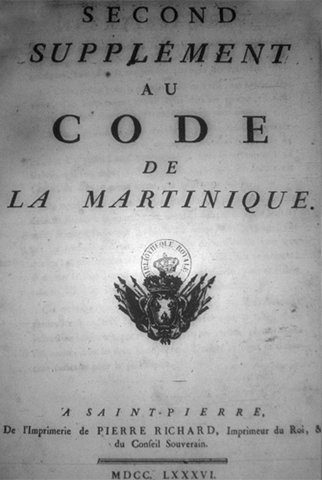

Pictures taken July 19th, 2007 in Annapolis by Author

[1] "Roger Brooke Taney." DISCovering U.S. History. Gale Research, 1997. From Richard L. Hillard, "Roger Brooke Taney." Great Lives from History, Frank N. Magill, ed. American Series, Vol. 5. Salem Press, 1987. Reproduced in History Resource Center. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group.

http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/HistRC/ (Document Number: BT2104101109)

[2] R. Kent Newmyer. John Marshall and the Heroic Age of the Supreme Court. Southern Biography Series. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001. xviii + 511 pp. Illustrations, essay on sources, index, list of cases. $39.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8071-2701-8.

[3] Vernellia R. Randall ; University of Dayton School of Law

[4] Professor Yvette M. Barksdale; Associate Professor of Law, The John Marshall Law School

[5] Professor Yvette M. Barksdale; Associate Professor of Law, The John Marshall Law School

[6] Professor Yvette M. Barksdale; Associate Professor of Law, The John Marshall Law School

[7] Roger Brooke Taney; J.P.W. McNeal. Transcribed by Douglas J. Potter.; The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume XIV. Published 1912. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Nihil Obstat, July 1, 1912. Remy Lafort, S.T.D., Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

[8] Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library;

http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/JefVirg.html[9] [9] "Roger Brooke Taney." DISCovering U.S. History. Gale Research, 1997. From Richard L. Hillard, "Roger Brooke Taney." Great Lives from History, Frank N. Magill, ed. American Series, Vol. 5. Salem Press, 1987. Reproduced in History Resource Center. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group.

[10] The Taney Court; The Supreme Court Historical Society

[11] Roger Brooke Taney. "Dictionary of American Biography Base Set. American Council of Learned Societies, 1928-1936. Reproduced in History Resource Center. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group.

http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/HistRC/ (Document Number: BT2310002363)

[12] Roger Brooke Taney ."Dictionary of American Biography Base Set. American Council of Learned Societies, 1928-1936. Reproduced in History Resource Center. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group.

http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/HistRC/ (Document Number: BT2310002363)

[13] "Roger Brooke Taney." Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2nd ed. 17 Vols. Gale Research, 1998. Reproduced in History Resource Center. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group.

http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/HistRC/ (Document Number: K1631006393)

[14] Roger Brooke Taney. "Dictionary of American Biography Base Set. American Council of Learned Societies, 1928-1936. Reproduced in History Resource Center. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group.

http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/HistRC/ (Document Number: BT2310002363)

[15] Roger Brooke Taney. "Dictionary of American Biography Base Set. American Council of Learned Societies, 1928-1936. Reproduced in History Resource Center. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/HistRC/ (Document Number: BT2310002363)

[16] Roger Brooke Taney. "Dictionary of American Biography Base Set. American Council of Learned Societies, 1928-1936. Reproduced in History Resource Center. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/HistRC/ (Document Number: BT2310002363)

[17] Infamous Dred Scott slavery case decision took place 150 years ago this week

kansiscitykansan.com; Thursday, March 8, 2007 BRYAN F. Le BEAU

[18] Roger B. Taney; From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

[19] We the Slave Owners;

Dinesh D'Souza; Copyright © 2007 by the Board of Trustees of Leland Stanford Junior University

[20] The Supreme Court Historical Society

[21] Roger B. Taney; From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

[22] The Taney Court; The Supreme Court Historical Society